Want to clear a room quicker than a toddler with a runny nose? Just bring up the carbon tax. You’ll get the same response: a mix of shifty eyes, uncomfortable coughs and maybe a few defenders.

No matter what you think about the tax, however, it’s still here, and it’s making life in Canada more expensive with every passing year.

It’s been just over five years since the federal government made carbon pricing mandatory in every province and territory across Canada — and the carbon tax has been a hot topic of discussion ever since.

The Canadian carbon tax is a fee the government charges on activities that produce carbon emissions. The government introduced the tax with the hope that by charging people for emissions (e.g. taxing you when you fill up your car with gasoline), Canadians would change their behaviour and ultimately look for alternatives.

Behaviour changes could include trading your gas-powered vehicle in for an electric vehicle or upgrading your home to near-net-zero by installing solar panels and energy-efficient appliances. However, while these may seem like simple solutions on paper, the regional and economic realities make these measures cost prohibitive for many Canadians struggling with affordability.

We wanted to look at how the carbon tax is doing across the country and assess whether it’s having its intended impact five years in.

We conducted research across Canada earlier this year and found that nearly half (48 per cent) of engaged women oppose the carbon tax, seeing it as a lofty policy that doesn’t translate to real change — just higher bills from using gasoline to drive, natural gas to heat our homes and propane for cooking on barbeques.

Engaged women aren’t the only ones who think the carbon tax isn’t working.

“I think it has served a purpose up until now,” former Bank of Canada governor Mark Carney said in May, and it’s now time for a “credible and predictable” alternative.

So, what does the current system look like, and what are the alternatives?

Unpacking the carbon tax and how it works

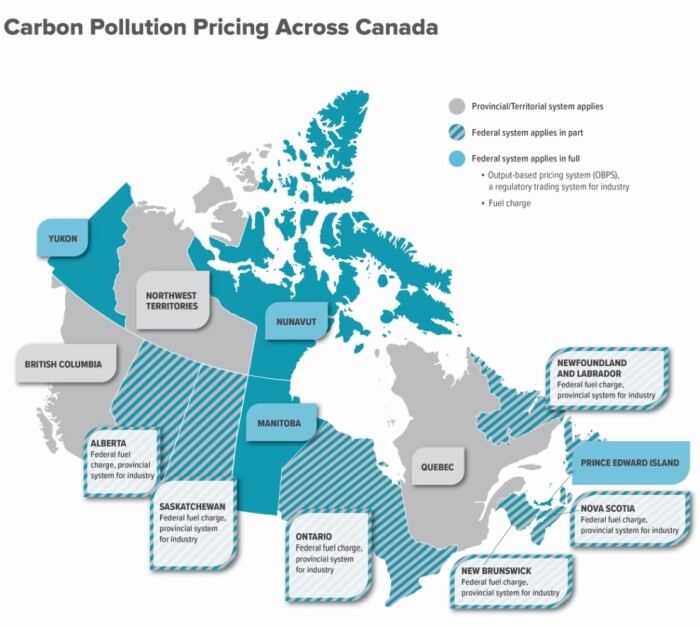

The federal carbon tax was introduced in 2019 for provinces and territories that didn’t already have their own carbon pricing system or had systems in place that didn’t meet federal benchmarks.

Back then, the provinces and territories were given three options: adopt the federal pricing system entirely, design their own pricing system tailored to local needs but in alignment with the federal guidelines or opt for a hybrid approach.

In Manitoba, Nunavut, Prince Edward Island and Yukon, the federal system applies in full (fuel charge and OBPS).

Alberta, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Saskatchewan all follow a hybrid system — the federal fuel charge is in place, and there is an independent provincial system for industries.

Quebec, British Columbia and the Northwest Territories have all implemented independent carbon pricing systems based on the benchmarks set by the federal government to ensure they are comparable and effective.

This means the carbon tax doesn’t look the same for every Canadian, so let’s break down the top three models.

(1.) The federal carbon tax

The federal pricing system has two parts:

- The “fuel charge” — a regulatory charge on fossil fuels

- An output-based pricing system (OBPS), a performance-based system for industries

Canadian carbon pricing map. Image credit: Canada.ca

The fuel charge applies to fuels like gasoline and natural gas, while OBPS is designed for industries that emit greenhouse gases.

The federal carbon tax adheres to the pricing guidelines set by the Government of Canada for emissions resulting from the burning of fossil fuels. In April of this year, it increased to $80 per tonne and is slated to increase by $15 a year until 2030, when it will reach $170 per tonne.

What does that mean for the cost of gas and home heating?

The April increase resulted in an additional 3.3 cents being charged on a litre of gasoline and 2.9 cents to a cubic metre of natural gas in provinces where the federal system applies in full.

Under this system, eligible individuals and families receive the Canada Carbon Rebate (CCR), a quarterly tax-free installment to offset the increase in prices that result from the carbon tax. According to the federal government, approximately 90 per cent of the proceeds are returned to individuals through the CCR, while the remaining 10 per cent is distributed to farmers, small- to medium-sized enterprises and Indigenous governments.

Despite these quarterly rebates, consumers and companies in these regions are feeling the squeeze. The increased cash flow required to maintain business as usual in industries like transportation and agriculture is being passed down to the consumer as products become more expensive due to the tax.

(2.) The cap-and-trade system

The cap-and-trade system in Quebec, established in 2013, sets an annual limit (or cap) on total greenhouse gas emissions from industries like electricity production, fuel distribution and industrial operations. Over time, this cap is lowered to encourage companies to reduce their emissions.

Each company is given a certain number of emissions allowances, but if they need more, they must buy additional allowances either from a government auction or other companies. Companies that reduce their emissions can sell their surplus allowances at market prices. Those that fail to meet their targets must purchase extra allowances or face penalties.

The revenue from carbon market auctions is reinvested in sustainable infrastructure and initiatives.

While this system focuses primarily on industry, individuals and families in Quebec feel the effects through increased costs of goods and services as businesses pass down the costs of purchasing emissions allowances.

(3.) Provincial carbon tax and OBPS

In British Columbia, the provincial government has implemented its own system that aligns with federal climate regulations.

B.C.’s carbon tax was introduced in 2008 at $10 per tonne, well before the federal carbon tax. The province’s fuel charge and output-based pricing system (OBPS) are regulated by the provincial government.

As of April 2024, the carbon tax in B.C. is on par with the federal tax at $80 per tonne. While B.C. residents do not qualify for the federal Canada Carbon Rebate, they receive a provincial rebate based on income. The rebate is capped at incomes of $41,071 for individuals and $57,288 for families. Those earning below these thresholds receive the maximum rebate, with the amount gradually reduced by 2 per cent for incomes above the limit until it phases out completely.

Essentially, in B.C — the more you make, the less you get back.

Which carbon tax system works best?

Opinions on carbon pricing vary widely, influenced by regional, economic and environmental factors.

Some don’t believe in the legitimacy or effectiveness of carbon tax at all.

Some support a straightforward carbon tax like the federal system, which directly increases fuel costs and provides rebates to offset the impact on households. Proponents argue that this approach creates a clear financial incentive to reduce emissions, making it easier for individuals and businesses to understand and adjust their behaviors.

However, for many who lack the means or practical ability to change their habits, the carbon tax can feel less like an incentive and more like an added financial burden. For example, running out and getting an EV, or changing someone’s home to net-zero is costly and not in the cards for many people. The federal carbon tax also faces criticism because tax is added on top of it when it’s applied. For example, when you get gas for your vehicle, GST is added on top of the carbon tax — essentially a tax on the tax.

In August, the Canadian Taxpayers Federation released polling results that showed 62 per cent of Canadians want that tax on the tax to be scrapped, and estimates show that if it were, Canadian taxpayers would save $595 million this year and more than $1 billion annually by 2030.

On the other hand, cap-and-trade systems, such as the one in Quebec, appeal to those who prefer market-driven solutions. Supporters believe that it offers more flexibility while potentially reducing emissions more efficiently by allowing companies to trade emission allowances.

There is no perfect system, and deciding which one is “better” depends on the goals of the policy and the context in which it is applied. A carbon tax is more predictable in its costs, while cap-and-trade can potentially reduce emissions faster but may be more complex to manage.

Is there a carbon tax alternative?

One alternative to carbon taxes that has gained traction in other countries is Germany’s renewable energy surcharge and investment approach.

Rather than solely relying on carbon pricing, Germany focuses on subsidizing renewable energy development and incentivizing energy efficiency where public and private investments are made into renewable technologies like wind, solar and electric infrastructure.

This approach has garnered strong support because it emphasizes the development of renewable energy and creates jobs, while also recognizing the practical realities of requirements for oil and gas use. This model offers an example of how proactive investment in renewable technologies, combined with policy incentives, can attract more widespread public approval while still achieving long-term emissions reductions.

As Canada moves forward with climate policy, finding the right balance between effectiveness, fairness and economic impact will be key to securing broad public support for whichever approach is used.

Despite the introduction of various carbon pricing mechanisms across Canada, none have succeeded in changing consumer or business behaviour on a large scale. And as we learned in our research, 2.6 million women across the country do not support the carbon tax, highlighting how these systems fail to address the deeper economic and social factors that drive emissions.

To Carney’s point, the carbon tax may have served a purpose — but now it’s time for a credible alternative that prioritizes incentives rather than creating additional financial pressures.